Among the many factors that govern Medicare funding and expenditure, the Sustainable Growth Rate (more commonly referred to as SGR) formula has historically ranked amongst the most important. Simply put, SGR had been used to dictate the increase in physician compensation for services performed under Medicare, up until the implementation of the Medicare Access and CHIP Authorization Act (MACRA) of 2015-which now determines physician pay based on the merit/quality of service and/or alternative payment models (e.g. lump sum incentives or annual payments.). Originally, SGR was conceived as part of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997.[2] Its main focus was to control the yearly increase in spending on physician services.

Despite its recent replacement with MACRA, it is easy to see how important SGR was in light of the over $555 billion dollars spent on physicians services in the United States in 2010-for Medicare services alone this number is estimated to be about 110 billion dollars. But what exactly was SGR? As mentioned above, SGR was a formula that attempted to determine how much physician services should increase. Specifically, the SGR formula took into account three factors: the cost of physician services (based on a national level), Medicare enrollment, and the GDP. In 2003, the MMA (Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act) slightly modified the SGR by taking into account the estimated 10-year average annual percentage change in real GDP per capita. Increases in physicians costs (due to advanced technology, new regulation, or increased demand), increased Medicare enrollment, and increases to GDP all resulted in increases to the SGR.[1] Importantly, the SGR was designed to discourage overcompensation. In fact it included a clause specifically designed to discourage such behavior, which essentially stated that if spending for all physicians in Medicare in a given year exceeded the prior year’s SGR target, then the amount paid to physicians in the next year would be reduced in order to hit the SGR target. In a local context, anesthesiologists and anesthesia service providers performing services under Medicare would ideally be incentivized to keep costs under the SGR target. However, since physician costs were determined based on the total cost of physician services provided, local anesthesiologists and anesthesia service providers in reality had no incentive to lower costs.

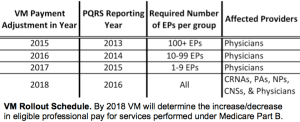

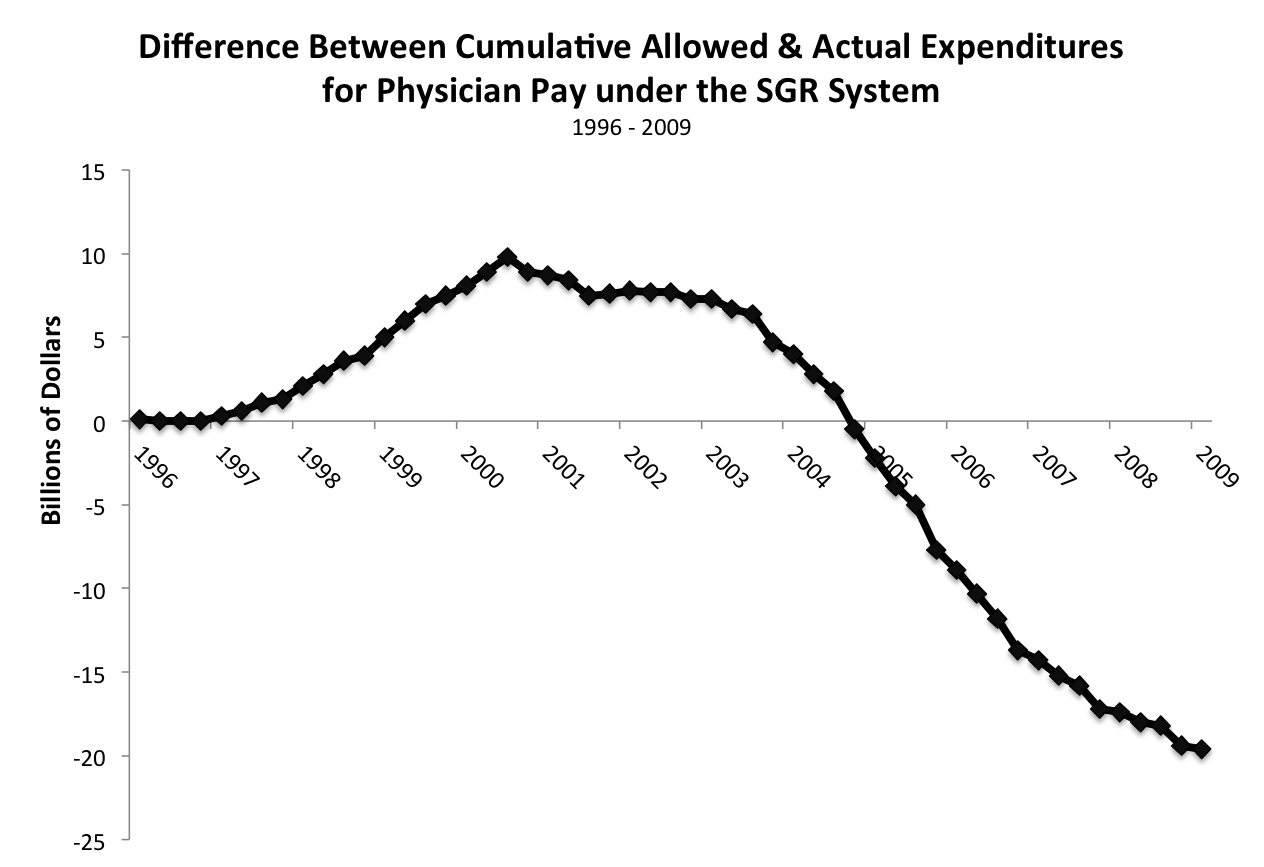

As a result, this key feature of the SGR was not enforced throughout its history. As Figure 1 demonstrates, actual physician expenditures outpaced SGR targets starting in early 2005- in part because of special interest lobbying. The net result of this lobbying resulted in Congress enacting a series of temporary “SGR fixes” that delayed the required cuts to physician spending. After a series of “SGR fixes”, which further delayed the required physician spending cuts (while not altering the underlying SGR formula), the SGR formula required a 24% reduction to physician payments (an estimated $117 billion dollars in cuts implemented over a decade). In order to avoid this dramatic reduction in physician pay, Congress enacted MACRA in 2015 to shift physician compensation away from the SGR formula. Instead, physician compensation is now based on the merit(MIPS)/quality of service and/or alternative payment models(APM). Whether these programs fall victim to the same perils as SGR, however, is yet to be determined.